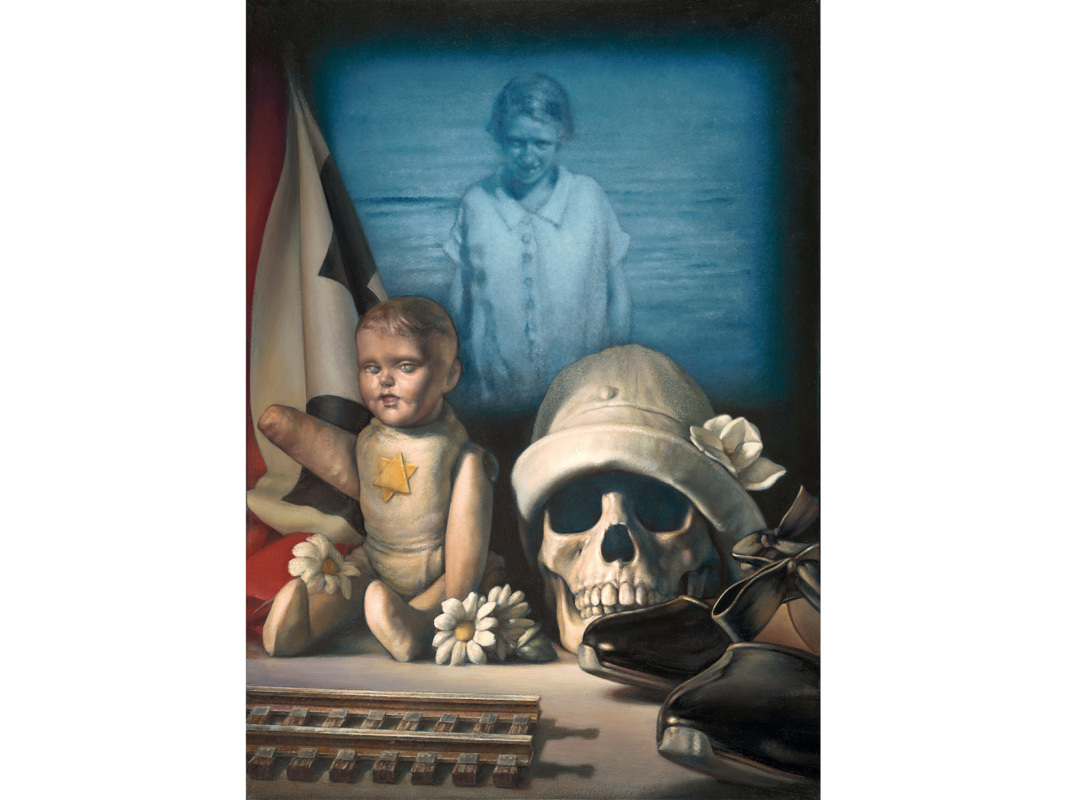

“Requiem For Annemarie,” Geoffrey Laurence, 2019, oil on canvas, 36” x 26”

The weighted tragedy of knowing of the murder of a relative that one actually never got to meet reverberates through “Requiem for Annemarie, 1936,” an oil-on-canvas work by Geoffrey Laurence, from Santa Fe, New Mexico. Laurence’s father was a Holocaust survivor who directed his rage against the overturning of his life more at his own Judaism than at the Nazis; he wouldn’t allow his wife to cook with garlic, because, he said, “it smells like the ghetto.” It was not until adulthood and his developing career as a painter that Geoff came to terms with his Jewish identity, and many of his works over the years have been focused on aspects of the Holocaust, usually at a masterful distance.

This work, however, represents a strong step in an altogether different, personal, direction. Anne-Marie was his father’s older sister. In 1936, she committed suicide at age 22—as did her parents (two of the artist’s grandparents) shortly thereafter—rather than wait to go to Auschwitz. She left behind two small children. Laurence knows about this through the other side of his family—his mother was also a Holocaust survivor—because his mother’s father, his other grandfather, was the head of the Jewish Hospital in Breslau and some of his colleagues in Berlin informed him. This was rather early in the era of accelerating persecution of Jews by the Nazi regime; two years later Anne-Marie’s widowed husband re-married—an Aryan woman—but he and the children were still at risk. He tried for days to get exit visas for them all at the police station—which saved him, thanks to an uncharacteristic glitch in the Nazi system. When the SS came to the door with his name and that of the children on the transport list, his wife told them that he was at the police station, and they mistakenly assumed that this meant that he had already been picked up, with the children, by their Gestapo colleagues. When he got home—with the exit visas finally in hand—he grabbed the kids and left and was able to find his way to America. This is why, as Laurence notes “my cousin is still alive in a home in Florida”—instead of having turned to ashes 80 years ago.

The haunting image depicts his aunt, perhaps at the seaside, at an earlier, happier time, in an old photograph, squinting from the sun—presented as if in a cinematic day-for-night mode, a blue filter covering the camera lens, transforming her into an almost ghostly backdrop presence. Most of the middle-and foreground elements are, in spite of being depicted in full color, inherently colorless: the swatch of train track (a simultaneous allusion, through its size, to children’s toys, and yet also to the Holocaust and its infamous train tracks); the shiny black shoes, the skeletal head wearing precisely the sort of hat with its jauntily-placed blossom that one can imagine Anne-Marie wearing in her late teens and early twenties only a few years before Hitler’s regime began to strangle Germany; the stripped-down doll with its lifeless blue eyes and extended right arm (almost, one might say, in a Nazi salute),without a hand. But there are spots of real color: the yellow six-pointed star on the doll’s chest, the central element in the daisies (of the same yellow, in subtle irony)—and the black and red components of the Nazi flag. This is a small and concise world of memory and imagined memory.

Geoffrey Laurence is an American realist painter. He lives and works in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Born in Paterson, New Jersey. Child of Holocaust survivors, he was brought up and educated in London, England. He attended the Byam Shaw School of Art (1965- 68) with Bridget Riley and Bill Jacklin, receiving his LCAD. He studied graphic design under Tom Eckersley at London College of Printing 1968-69, BFA in painting at Saint Martins School of Art (1969-72) under Frederick Gore and MFA Cum Laude at New York Academy of Art (1993-95) with Eric Fischl, Wade Schuman and Vincent Desiderio. He is the recipient of grants from The George Sugarman Foundation, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, the Walter Erlebacher Award and a J. Epstein Travel Award. He has exhibited across the USA and in Europe including the Las Vegas Art Museum, Yeshiva University Museum and the Arnot Art Museum and currently at the Museum of Biblical Art (Dallas). A retrospective of his Holocaust Series work was exhibited at the Fulginiti Pavilion at Anschutz Medical Campus in 2016, and he is currently represented by RJD gallery in NY. To learn more about Geoffrey, visit his website geoffreylaurence.com and follow him on Instagram @geoffrey_laurence.