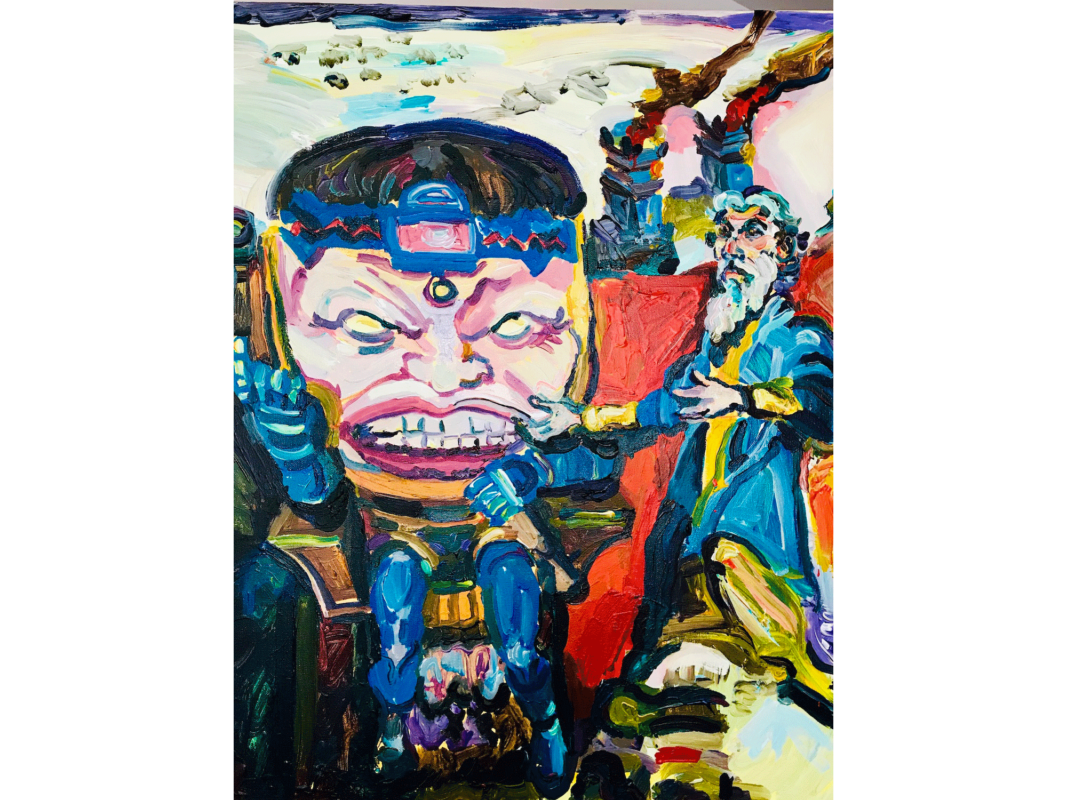

“Moses Meets Modok,” Joel Silverstein, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 24” x 30”

One of the issues of particular interest—both in the sweep of work by Jewish artists in general and certainly where this exhibition is concerned—is the range of materials and stylistic approaches taken toward biblical subject matter. Joel Silverstein, from Mahwah, New Jersey, has long engaged in a vibrant, expressionistic, color-powerful, stylized attack in oils on his canvases. One of the more unique and fascinating aspect of his paintings is his interweaving of biblical imagery—often in a manner that alludes to the depiction of a given subject in the previous centuries of Western art—with direct and indirect references to the popular culture, specifically the comic-book culture with which he grew up, as did many kids in the 1950s and 1960s.

Nowhere is this more vitally evident than in his “Moses Meets Modok.” Modok is one of Marvel comic books’ all-time great villains. He was originally conceived as Modoc—an acronym for “Mental Organism Designed Only for Computing”—because, as a former employee of Advanced Idea Mechanics, (an arms-dealing organization specializing in futuristic weaponry), he underwent substantial mutagenic medical experimentation originally designed to increase his intelligence. The success of the experimentation led to his freakishly overdeveloped head. This provides the character with his signature look, together with a flying chair into which he is strapped, for mobility. However, after the experiments, he rebelled against his masters, killing them all and taking control of AIM. He also changed his name and his purpose to “Mental Organism Designed Only for Killing”: Modok. Debuting in 1969, during the Silver Age of Comic Books, Modok has appeared in over four decades of Marvel continuity, pitting his profoundly evil personality most noticeably against Captain America, The Hulk, and Iron Man.

Silverstein pits him against Moses. The quintessential spiritual hero within the Jewish tradition (and no physical weakling, mind you—just ask the Egyptian taskmaster whom Moses killed with one blow, or the Midianite shepherds whom he singlehandedly drove away from the well where Tzipporah and her sisters were trying to get water for their flocks) is dwarfed in physical size by Modok. Of course, this merely underscores how the warriors of the Lord don’t require the convention of physical size to be victorious. Indeed, this size-disparate meeting connects Moses most obviously to his spiritual descendant, David, who felled the Philistine giant, Goliath (Modok’s physical ancestor, so to speak), with a stone from his sling, because he was “filled with the spirit of the Lord” (I Sam 17:45-7). Moses could easily outdo the priests of the pharaoh—what appear as two altars with smoke rising from them, behind Moses, also connect him to another spiritual descendant, Elijah, who defeated all of the priests of Ba’al singlehandedly with a simple prayer to God, who ignited the wet kindling of Elijah’s offering—and so Moses shall prevail against Modok. The idea, that when Jews have prevailed historically it has been due less to physical prowess than to intellectual/spiritual process, extends from the past and Moses to the future and Modok in this moment outside of everyday time, place, and circumstance.

While the biblical narrative follows a linear chronological trajectory, the author of that narrative, in traditional terms—God Itself—does not. After all, as God explained to Moses when they had their first encounter, at the Burning Bush: “I am/will be that I am will be”—my Name is Being/Isness Itself, which has no boundaries in time and space that can be contained by an ordinary name. Not only God, but the understanding of God in the Hebrew Bible: the all-encompassing creator of Genesis 1 is reduced in understanding, by the time Jacob has his first dream out in the wilderness, as he flees his brother Esau’s anger, to a being whom Jacob is surprised to find away from his father Isaac’s domain: he understands God to be both localized and personal; later on, the Israelites who follow Moses through a different wilderness regard God as national—indeed God commands them merely to “have no other Gods before Me”; they are not commanded to believe that no other Gods exist. Only later, in the exile to Babylonia between the destruction of the First Temple and the return from exile and building of the Second Temple do their Judaean descendants come to recognize the universal singularity of God and God’s power.

Between Jacob and Moses is the narrative of Joseph—as we have noted. And of all the sub-narratives of sibling relations, from Cain and Abel to Moses and Aaron and Miriam, none describes as perfect a circle of drama as does that of Joseph and his brothers. The dreamer becomes the dream-interpreter becomes the witness of the enactment of his dreams; the Midianite traders who purchased Joseph from his brothers will have a descendant named Jethro, a priest, whose daughter, Tzipporah, will end up married to Moses—who, in keeping his father-in-law’s flocks, will encounter God within the Burning Bush and emerge as the prophet of prophets for Israel. The facilitators of the story that will lead from Canaan to Egypt and from Joseph to Moses will be the brothers, led by Judah—ancestor of Kings David and Solomon—who sell Joseph to the Midianites.

Joel Silverstein was born in Brooklyn, NY in 1957 and attended Pratt Institute BFA in Painting 1979, MPS in Art Therapy 1981, and Brooklyn College MFA in Painting 1992. He has shown nationally and internationally at JADA, Miami Art Basel, the Van Leer Institute, The Mishkan Le’Omanut Museum, The Bronfman Center, the Derfner Museum of Judaica, the Amstelkirk Gallery in Amsterdam, and the Jerusalem Biennial (2015 and 17.) The artist/ critic is a Founding and Executive Member of the Jewish Art Salon and has curated or advised on 15 Salon exhibitions including: Through Compassionate Eyes; Artists Call for Animal Rights at the Charter Oak Center, Hartford Ct., POW!!! for Jewish Comic Con, The Dura Europos Project, both at the Philadelphia Museum of Jewish Art and UJA NY. Recent exhibitions include The Beth Sholom Judaica Museum, Roslyn NY, The Clemente Center, NY, the Pratt Hadas Gallery Rohr Center, The Columbia/ Barnard Kraft Center. He has presented at The Conney Conference of Jewish Art at the 92nd Street Y, and the Association for Jewish Studies Annual Conference in 2019. Joel’s work and curated exhibitions are cited in Ori Z. Soltes’ Tradition and Transformation; Three Millennium of Jewish Art & Architecture, 2016 and Matthew Baigell’s Jewish Identity in American Art, 2020. To learn more about Joel, check out his website www.joelsilversteinart.com and follow him on Instagram @joelsilversteinart.