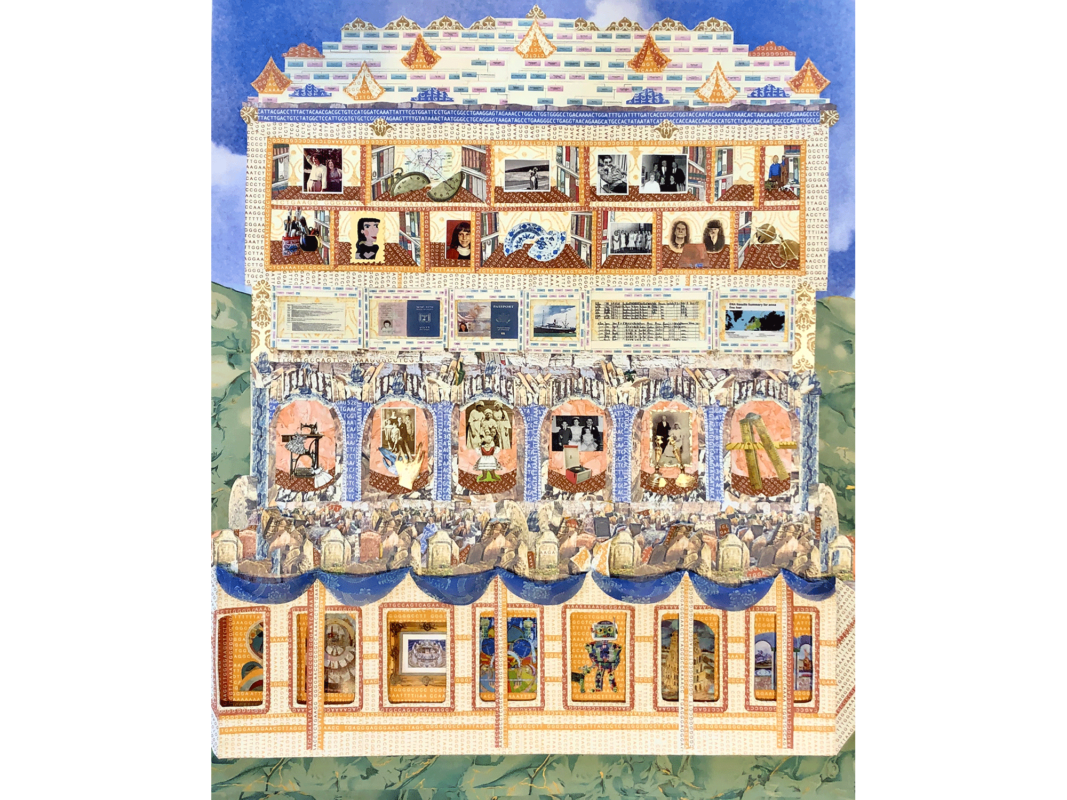

“Chana’s Beys haChaim Muzey/חנהס בית–חיים מוזיי,” Anna Foer, 2020, collage, 28″ x 22″

One could hardly find a more overwhelming visual marriage between personal and familial history and identity on the one hand and the sweep of Jewish history on the other than in Baltimorean Anna Foer’s towering collage of “Chana’s Beys haChaim Muzey”—that is: “Anna’s House of Life Museum.” From some distance one sees a large, multiple-storied edifice against the backdrop of green mountains (their color echoed in the street before the structure) and bright blue skies, with a porch extending out over the sidewalk, held up by slender pillars. “Windows” at different levels allow one to see people and objects. The collage of subjects proves, with a closer look, to be what the title of the work suggests: a museum of sorts, in which the life of the artist as it relates to the history of her family and to Jewish experience is displayed. The overall richness of this work, in color, form, and concept is underscored linguistically by the title that spills out in three linguistic ripples: the artist’s first name in Hebrew, but with an anglicized possessive suffix; the words “House of life” in a Yiddishized deformation of Hebrew; and the word “Museum” as that universal word would be articulated in Belarus.

One discerns across the museum surface a succession of letters—a text of sorts—that repeat themselves as an abstract pattern assuming varied coloristic form throughout the work. This, it turns out, is Foer’s genetic code, which serves as the brick slabs that hold the entire structure together, from pillars—and the sidewalk into which they are embedded—to roof line. The roof itself, offering a series of seven pointed turrets and six “blunted” ones (the one connoting creation with the Sabbath, the other without the Sabbath, among other ideas) also contrived of that code, is primarily made up of an intricate weave of blue and violet “shingles”—placed against a white ground and connected by delicate tendrils—that constitute the artist’s extensive family tree.

These fundamental elementa, of expansive self, frame an intriguing archive of personal images: on the one hand an array of older black and white photographs of family members alone or in groups—and what we can readily assume, given the context, is an elementary school photograph in color of the smiling artist of the sort that virtually every kid in the American suburbs of the past two generations acquires and keeps or eventually forgets about in some drawer along the winding path of his or her life. The three levels of archival “display” also present references to the artist’s own earlier artwork over the years, and, centrally placed, a pair of the artist’s own passports—one Israeli and one American, underscoring her sense of double identity.

Second, and next to these, on the same second “floor” of the Museum, are the 1930 and 1910 census forms that include her father in the latter case, and her maternal grandmother in the earlier one—together with the image of a ship on which one might imagine some of her relatives from that earlier era or earlier still, arrived from Belarus; the reference to that corner of the Old Country in which her family resided for generations is found in the repeating array of gravestones from a Jewish cemetery in Belarus. These stones in turn lead the mind to the array of colorful but broken objects—flotsam and jetsam that includes sunglasses, a pocket watch, and a pretty china dish—that allude to the destruction of Ashkenazi Jewry in Europe culminating with the Holocaust that began not very long after that more recent census.

Anna Fine Foer decided she was going to be an artist when she was 11 years old when she lived in Paris, visiting every museum and gallery in the city. She studied fibers at Philadelphia College of Art. Anna worked as a textile conservator in Haifa and Tel-Aviv. She studied textile conservation at the Courtauld Institute in London. Back in the US, Anna worked in conservation for the Textile Museum in Washington, D.C and as a freelance textile conservator. At the same time, she continued to construct collage landscapes with scientific, political and meta-physical significance. Anna now lives in Baltimore and has two adult sons. Her work has been exhibited at the Indianapolis Museum of Art and is in the collection of the Haifa Museum of Art and the Be-er Sheva Biblical Museum. She was awarded a prize for the Encouragement of Young Artists in Jerusalem and received a Maryland State Arts Council grant for Individual Artists in 2008 and in 2016. To learn more about Anna, visit her website www.annafineart.com and follow her on Instagram @afineartiste.