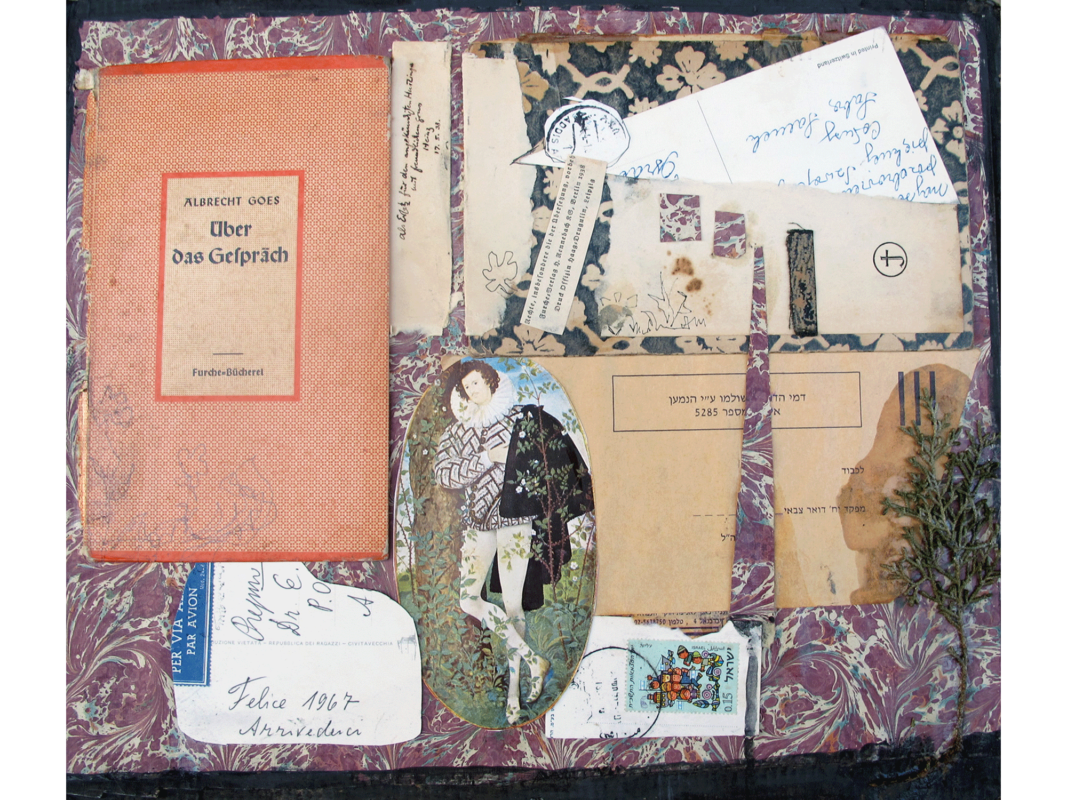

“About the Conversation,” Heddy Abramowitz, 2017, mixed media, collage, 30 x 36 cm (11 3/4 x 14 inches)

It goes without saying—and yet I am saying it—that notions of Jewish identity and authenticity, whether expressed visually or otherwise, whether intersecting the question of defining “Jewish art” directly or obliquely, can be approached from angles other than biblical, rabbinic, historical, or familial. While in the broadest sense, all of these discussional facets may also be called “cultural,” one might, for the sake of convenience, examine certain expressions as offering a specific—and thus, in a sense, more narrow—cultural aspect. How might one characterize this? What are the particulars of what we might term Jewish cultural foci? How do the cultural issues intersect cultural—or spiritual (as opposed to religious)—values?

For starters, we might recall that the birth of the modern Zionist movement was marked by a debate regarding its goals, political or spiritual, and that spiritual Zionism developed a subset called cultural Zionism—this was the umbrella under which the Bezalel School opened in Jerusalem in 1906, for instance—with the avowed purpose of creating “Jewish national art.” Half a century later, the state of Israel was beginning to become a focus for diaspora and sometimes Israeli Jews, culturally as well as politically and spiritually, and the pulse of that focus has increased exponentially in the following half-century, up to the present time. On the other hand, diaspora Jews—and thus diaspora Jewish artists—have also pushed back against the supposition that there is no such thing as Jewish art, both simply by creating art and also by making art that reflects both seriously and humorously on the condition of being Jews in the diaspora. The pace of such explorations has also quickened, particularly in the last two generations—just as we have seen the pace of reflecting on the Holocaust intensifying during these same decades, (which I have chosen to subsume under the category of history).

One might begin the conversation of this sub-arc of the overall exhibition arc with a look at the mixed media collage, “About the Conversation,” by Jerusalem inhabitant, Heddy Breuer Abramowitz. Born in Brooklyn to Holocaust survivors, Abramowitz grew up in Maryland and moved to Israel in 1980, residing for many years in the Old Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem. Often urban landscapes, particularly Jerusalem, as well as the immigrant experience, the Holocaust, and the issue of Jewish women, have been her subjects. So, too, the issue of a disappearing literary culture and the individual’s relationship to writing and reading, of both literature and letters—translating, then, the familiar traditional Jewish focus on texts into a focus on a broader range of texts than are thought of traditionally as “Jewish.”

Kinship with a bygone era—how many of us still write letters, instead of emails or even just texts?—intersects a personalized version of a traditional Jewish, diasporic question: where and what is home? “My American, Jewish, European and Israeli identities all are layered with Catholic influences of my upbringing in a Christian area and attending college at a Jesuit university. German represents both a difficult homelife and family times, and contrasts to the German language associations with the Holocaust, and my family’s experiences.”

The work in the present exhibition places its components against a swirling backdrop of hand-marbled endpaper, creating an abstract, spaceless space. The artist has cut and torn a 1967 postcard—the year of the Six-Day War between Israel and her Arab neighbors—from Adis Ababa, Ethiopia, using part of it, on the upper right of her work, to present the form of a stylized house with roof, windows, doorway, and delicately drawn flowers that suggest a garden. Below this, to the lower right, a small sprig of real greenery is placed against an Israeli summons to military reserve service; the other end of the summons is obscured by an oval-shaped cut-out that presents a Renaissance-era dandy—as if he is some Shakespearean character, like the Duke of Orsino in Twelfth Night, leaning against a tree, surrounded and nearly obscured by vegetation.

Between that image and the sprig is a cut out of the same marbled paper, shaped like a cypress tree from Jerusalem, and at its base, (its “roots” one might say), an envelope fragment covered by an Israeli stamp decorated with the image of stereotypical, stylized Israeli children, wearing the sort of cap (called lovingly, in Hebrew, a kova tembel—“fool’s hat”) that was once associated with kibbutz-centered Israeli culture. Another fragment of the 1967 envelope, on which someone has written “Felice 1967, Arrivederci”; “Happy 1967, farewell,” in Italian, anchors the lower left side of the image, above which, decorated with the same delicate ink-drawn flowers that overrun the lower part of the “house” walls, is the cover of a book by Albrecht Goes, in German: Ueber das Gespraech—About the Conversation—from which the artwork derives its title.

Goes was a German poet, novelist, essayist, and theologian whose writing in the early 1950s—including his 1950 Holocaust novel, Burnt Victim, and his brief 1957 essay, About the Conversation—was considered pathbreaking within the process of reconciliation between German Jews and non-Jews, and more broadly between Germans and Jews; he was honored by the Berlin Jewish community with the Heinrich-Stahl Prize, in 1962, and received the Buber-Rosenzweig Medal in 1978. So Abramowitz’ conversation is not only about multi-lingual, multi-cultural, multi-national identity; it is about post-Holocaust thought and Israel being-in-the-world, and it is about diverse kinds of cultural literacy.

Heddy Breuer Abramowitz is a Jerusalem-based American-Israeli multidisciplinary artist. Born in Brooklyn, NY—daughter of Holocaust survivors—she was raised in southern Maryland near Washington, DC, moved to Israel in 1980 and lived many years in Jerusalem’s Jewish Quarter in the Old City. Recurring themes include urban landscape, introspective self-portraits, the Jewish woman, the immigrant experience, loss and commemoration and the Holocaust as legacy. She employs media ranging from oils to water-based paints to drawing media and may include embroidery, stone-rubbing, sumi ink, printmaking, photography and collages, as appropriate. Following academic degrees in international government and law, she initially was an observational painter. Her work has gravitated to personal subject matter; often allegory is used. It has evolved to things that go beyond words to the spaces in between them, sometimes enigmatic and defying precision. Abramowitz believes that the personal ultimately is universal. Visit Abramowitz’ website, www.heddyabramowitz.com and follow her on Instagram @heddybab. Be sure to like Heddy Abramowtiz Artist (@StudioHeddy) on Facebook, too.